Not a Farmer? Crop Insurance Matters to You, Too!

Crop insurance is the cornerstone of the farm safety net, protecting more than 490 million acres across all 50 states, as well as 136 crops and 604 varieties with 36 different plans of insurance. It has earned the trust of America’s farmers by providing personalized risk management plans that quickly deliver aid in the case […]

Crop Insurance Essential for California Farmers

For three years, California’s farmers and ranchers faced extreme drought. Then, this winter, as crop insurance agent Dan Van Vuren tells it, “It started raining in January and it didn’t stop until March.” It’s been a devastating year for many California growers, but crop insurance has provided a valuable safety net for our farmers, our […]

Farmers: Crop Insurance Provides Protection, Not Profit

America’s farmers don’t profit from crop insurance. They’d rather grow and harvest a crop than file a crop insurance claim. We recently shared an explainer demonstrating how crop insurance is an investment into the protection of family farms – not a get-rich-quick scheme. A brand-new series of interviews with farmers in the field confirms that […]

Misleading Claims About Crop Insurance Hurt Family Farmers

Farmers don’t profit from crop insurance. They’d rather grow a crop than file a claim. Crop insurance keeps America’s farmers growing after disaster. It’s the cornerstone of the farm safety net, and an integral risk management tool for family farmers. But activist critics are not afraid to use misleading claims to dismantle the farm safety […]

Private-Sector Delivery Protects Farmers

The Federal crop insurance program is built on a unique public-private partnership. Under this successful model, farmers purchase a personalized crop insurance policy from any of the private insurance companies – known as Approved Insurance Providers, or AIPs – authorized to sell and service crop insurance by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). But how […]

Farmer Support for Crop Insurance Key Theme at Farm Bill Listening Session

Between scoops of corn ice cream and live music, farmers and policymakers gathered yesterday at Minnesota Farmfest to discuss the issues that matter most to rural America. The Listening Session held by the House Agriculture Committee presented an opportunity for farmers, lenders, and other agricultural stakeholders to outline their priorities in the upcoming Farm Bill. […]

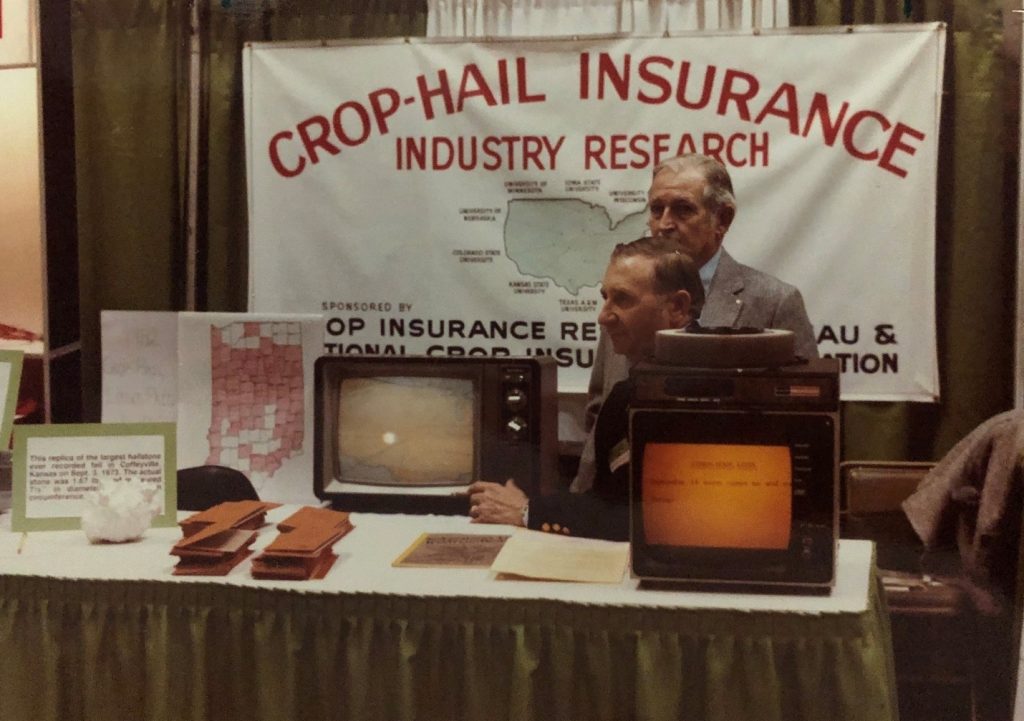

Celebrating 100 Years of Crop Insurance Research

Did you know this year marks 100 years of crop insurance-sponsored agricultural research? That’s right – crop insurance has supported American farmers for the last century, helping them manage risk and overcome obstacles, keeping our food supply safe and secure. In fact, over the past 100 years, National Crop Insurance Services (NCIS) and its predecessor […]

Farmer Participation in Crop Insurance Key to Farm Safety Net

Every day, farmers spend long hours working the land or caring for their livestock so they can provide high-quality food at an affordable price for millions of Americans across the nation. This amazing feat would not be possible without the critical safety net that crop insurance provides. However, instead of wanting to encourage more farmers […]

Crop Insurance by the Numbers

Crop insurance is the cornerstone of the farm safety net. Its unique public-private partnership is trusted by America’s family farmers and supported by voters. By delivering aid quickly when disaster strikes, crop insurance keeps family farmers growing, drives the rural economy, and supports our national food security. National Crop Insurance Services has put together 50 […]

Farmers Testify: Crop Insurance Works

President Dwight D. Eisenhower once famously said, “farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil, and you’re a thousand miles from the corn field.” That’s why farmers, crop insurers, and other agriculture stakeholders from across the country recently brought the corn fields to Congress. Farm leaders representing a diverse range of crops traveled […]